Intag: my program’s first expedition is to the cloud forest reserve about two hours northeast of Quito, in the province of Imbabura. In brief, fantastic. In less brief, I’m scared to write about it at all because I can’t possibly do it justice. Let’s start with the biodiversity:

At night, tenants would shine a light on a sheet to attract moths, which arrived in hordes. Try this in the U.S., and you might see five to ten species; do it in Intag, one of the world’s most biodiverse hotspots, and it’s impossible to count. Every time they do it, they see a new species. Those of us standing near the sheet gradually became festooned with moths – in our hair, on our faces, all over our clothes, and no two alike. It got to the point where I couldn’t lower my arms all the way for fear of crushing a hitchhiker. Some moths were surprisingly loyal, and stuck to my jacket all the way back to our cabin. One hid under my collar like a tiny bow tie.

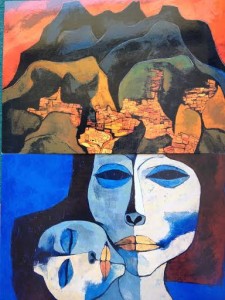

We spent the next day trekking through primary and secondary forest for about three and a half hours, getting to know the land. I’m pretty sure the elevation at Intag is even higher than Quito, so just imagine a light, up-and-down stroll across a small mountain range at ten thousand feet, replete with plants that have too many medicinal uses to count. Some were snacks for dinosaurs (see fuzzy mystery plants on the left). One tree, when nudged with the tip of a machete, secreted a thick blood-colored sap that could be used for sunscreen, treating wounds, repelling mosquitoes or making soap.

(Did I mention I got to use a machete? I’m an adult now!)

Biodiversity means equilibrium: lots of species, but low population density, so no single type predominates. Everything is in balance, a bit like a well-run democracy. And, like democracy, it is as valuable as it is fragile; altering or destroying a few little components can debilitate the whole system. This leads us to a caveat in this bio-paradise: the Ecuadorian government would like to mine the entire area for copper, in partnership with a Chilean company that owns the largest open-pit copper mine on earth (now 133 years old). Company’s catchphrase, according to an employee: “Desayunar cobre, almorzar cobre, dormir con cobre.” (Copper for breakfast, copper for lunch, copper at bedtime).

The trouble with copper is that it doesn’t sleep alone. It is commonly found alongside lead and arsenic, two of the more toxic by-products of extraction. Then there’s the mining process itself. In this case, it would be an open pit mine, which requires removing the overburden to get at the metal nested beneath.

When a mining company talks about “overburden,” they mean “ecosystem.” I’ll leave the catastrophizing to Bill McKibben, but suffice to say this struggle is far from over. The communities in this area are internationally known for having thrown out two mining companies who previously tried to establish operations here, but those weren’t backed by the state; this one is. The day we talked about activism and extractivism in Intag, a fellow visitor said something that struck home: tomorrow or in fifty years, someone will extract the copper under this forest. It may not even be this company, but as long as the global market demands copper, Intag will be under threat, because unlike money, copper doesn’t evaporate in times of economic strife. Stopping demand is the only real way to stop supply. And now I take ten million deep breaths.

Every leaf is about the size of a parasol. Or me in the fetal position, contemplating the global economic system.

On a lighter note: I ate bugs! Specifically, the larva of black soldier flies, frozen and baked and sautéed in lemon, with peppers. Good with guacamole. 4 out of 5 stars, would try again. And, because it would be sacrilege not to include dog pictures whenever I have them: