Currently listening to:

the perfect song for a lazy, wistful day,

where you’re already feeling nostalgic

for a city you’re still living in ♪ ٩( ´ω` )و ♪

🍑🍑🍑🍑🍑

Memories made for myself.

Memories made with friends I love,

as beautiful and evanescent as a breeze,

fluttering through a silk curtain.

Memories that will stay with me long after my stay at Oxford is over 🙂

Walking past Westgate, a shopping center at the heart of Oxford,

I saw that someone had set up an Alice-in-Wonderland-esque playground for kids,

complete with croquets and shiny little balls.

Could there be anything quite so Oxford?

Weather that calls for constant picnics.

We celebrated my friend Jess’s birthday by sitting on the grass in University Parks,

eating sandwiches, and sipping elderflower soda,

while Lou attempted a few card tricks that left us unexpectedly impressed.

The next day, I had another picnic with my friend Katie,

writing essays under the hot blaze of the suddenly bold sun.

Sometimes, the mere kiss of wind on your skin, the stir of spring through your hair,

is enough to make you feel acutely alive. Acutely happy.

I wish we had taken photographs that day, but it was also one of those moments

that don’t need to be captured so much as lived, and remembered, and cherished…

May your days be as full of mellow sunshine as we enjoyed that day, Jess 🙂

On a whim, I peeked into Oxford’s Museum of Modern Art the other day by myself.

They had an exhibition on the forces that shape and destabilize our ideas of home,

labor, equality, and the construction and deconstruction of cherished ideals.

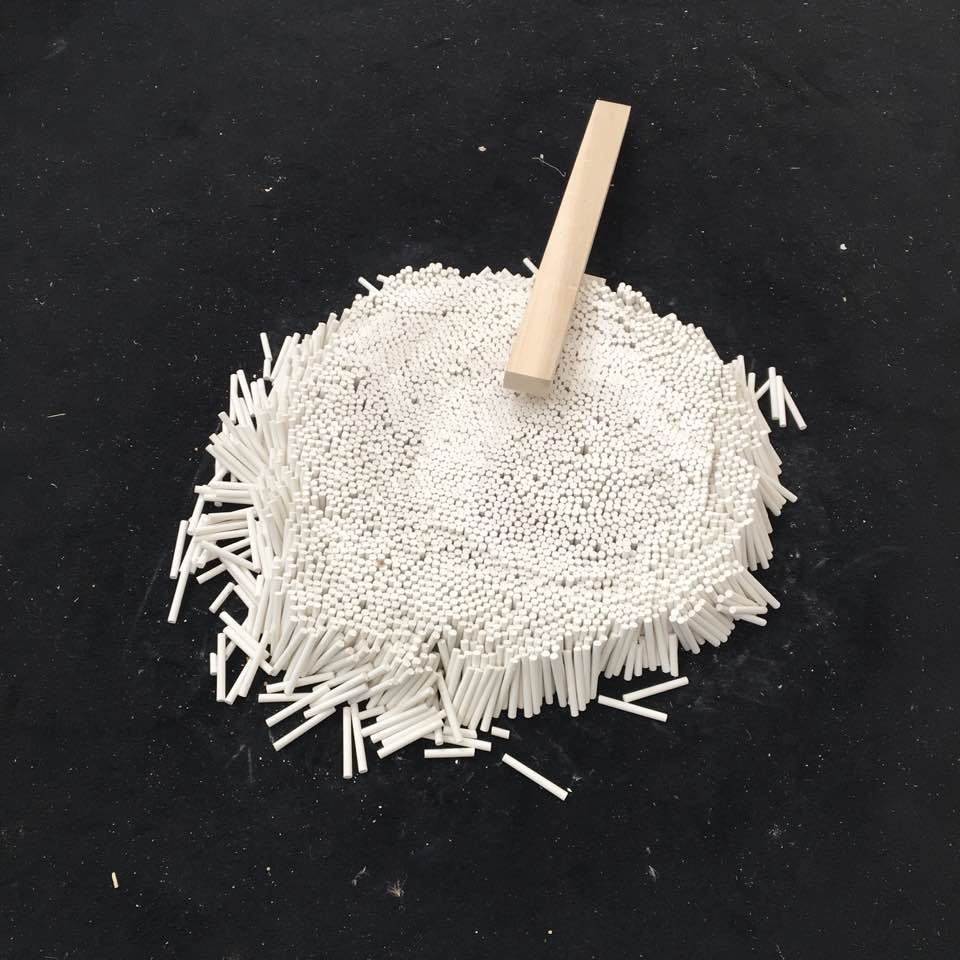

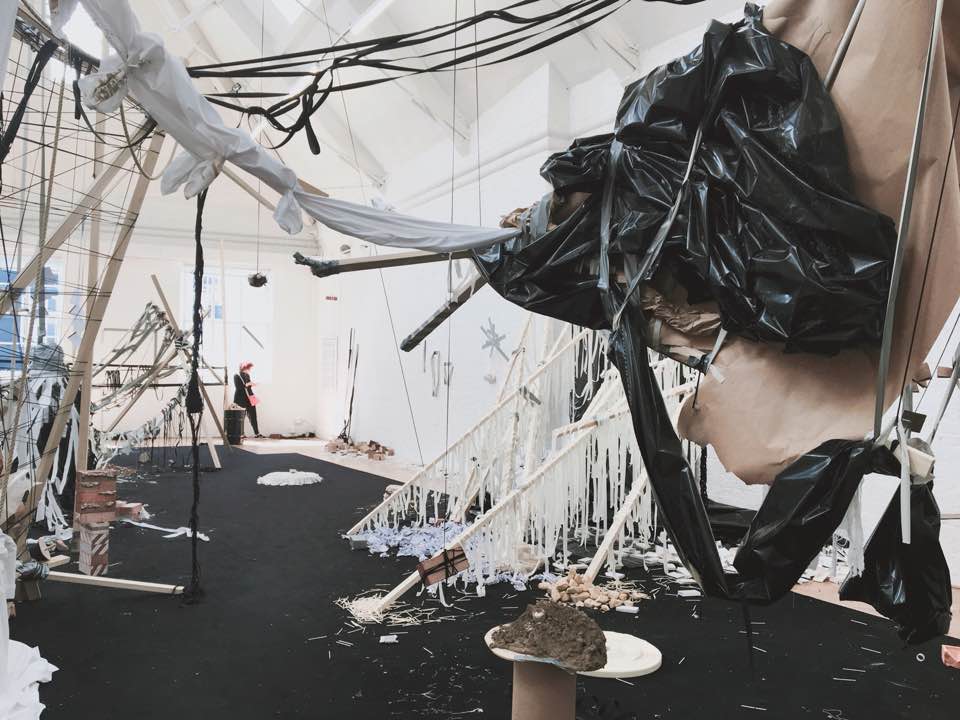

Disorder. Chaos. Materials for building scattered about like trash.

It left me with a feeling of deep sadness, although it was also very challenging.

Is there any way we can use the small and breakable lives we are given,

to build up, instead of causing disorder and disarray in a planet already splitting apart? 🙁

Lou, Jess, and I went to The Bear, a lovely old pub from the 13th century,

tucked away in a corner of Oxford. According to urban legend,

the pub is called “The Bear” because it used to have a hollow pit in the ground

where dogs and bears would fight while noblemen watched and placed bets. Hmm…

A little grisly, but the food was good, so I ate without moral compunction.

For two hours or more we launched into a fervent discussion of Harry Potter,

in which we began sorting everyone we knew into their respective houses.

I am, by all counts and preferences, a Ravenclaw.

“It just feels so right,” Lou said, laughing,

“that we’re sitting in a pub built hundreds of years ago, at Oxford,

sorting people into magical houses. Like it couldn’t be any other way.”

I couldn’t help but agree.

This week, my love affair with Blackwell’s Bookshop has reached an unconscionable extent.

Against my better judgment, my afternoons always end with my swerving into the bookshop,

drifting slowly around the mounds of beautiful paperbacks, picking up a random novel,

and getting (oh, deliciously) lost.

I’ve been reading almost a novel a day, and am so much the happier for it! 🍒

Rereading “My Name is Lucy Barton,” a novel by one of my favorite writers of all time

(Elizabeth Strout),

I nearly sobbed aloud in public.

Her writing never fails to be quietly, wrenchingly, unexpectedly moving,

conjuring deep warmth without unnecessary drama,

tugging at the heartstrings so quietly you don’t notice until all of your walls have come down.

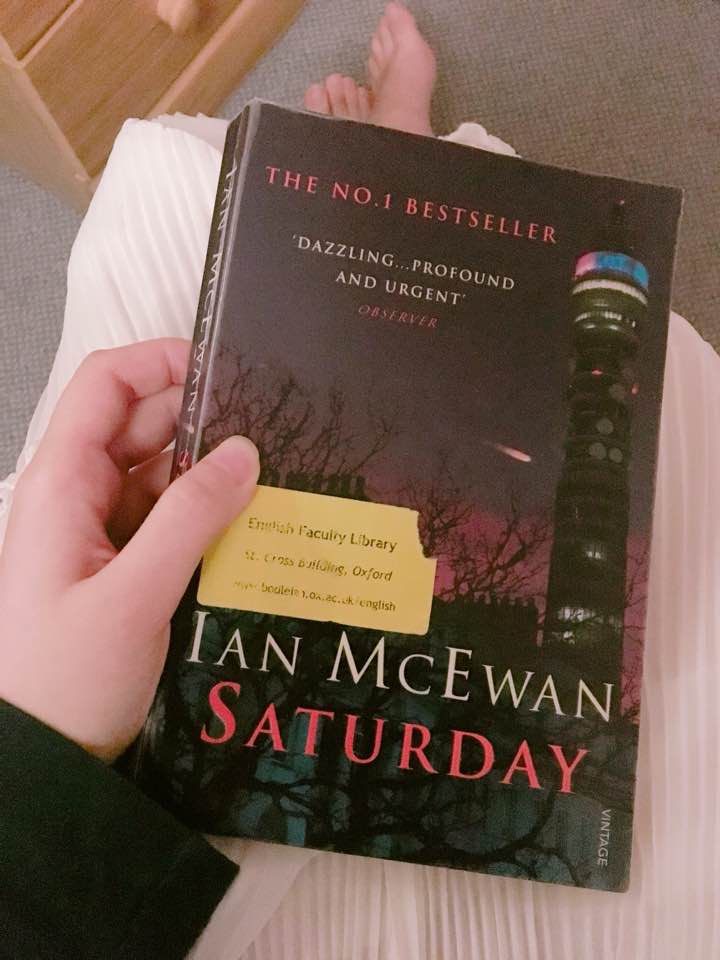

Back at my dormitory, working on my homework.

Reading McEwan’s descriptions of London protests while in England.

Thinking about our small outcry of free will against the looming backdrop of fate.

Was it fate that brought me to this city (or Fate with a capital F, as my tutor likes to say)?

It feels like it. It feels like I was meant to experience this place.

It feels, not as if I’ve worked my way here, but like a gift:

Spontaneous. Surprising at every turn.

Night falls slowly over Oxford, washing the pale old buildings with liquid blue.

Oh, how I love my days here.

How I love this life, wandering among mazes of book after book.

Goodnight, Oxford ✨

Goodnight. ✨

Goodnight ! ✨