[Warning: Long Post, but there is a prize for those who finish!]

Welcome back to The Greatest Hungarians! As I mentioned in my last blog post on this topic, Hungarians are an accomplished people. Before I get to the stories for this post, I thought I might just list some of the greats who I did not write about, but who deserve recognition:

- Ernő Rubik, inventor of the Rubik’s cube

- Béla Bartók, who collected Hungarian folk music and used it as inspiration for his innovative compositions

- Zsa Zsa Gabor, a Hollywood actresses of the 1950’s known for her personality, extravagance, and marriages (9 in total)

- Robert Capa, a renowned war photographer of the mid-20th century

- Ferenc Puskás, one of the best soccer players of all time, who led the Hungarian national team to international dominance and even defeated the British national team 7-1 in 1954

- Albert Szent-Györgyi. I had never heard his name before, but he discovered vitamin C by extracting it from peppers

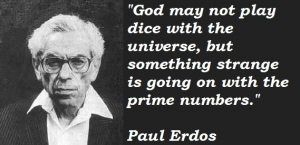

Now, I’ll introduce two of the most influential people to come out of Hungary: Paul Erdős and Franz Liszt. Be sure to read—or skip—to the end, because there are some excellent piano pieces composed by Liszt I think that you’ll want to hear!

~ ~ ~

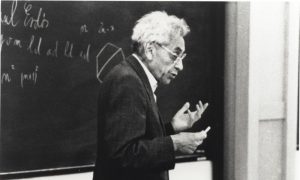

Paul Erdős (pronounced air-dish) is one of the most famous mathematicians of all time. Over the course of his career, he made major contributions to number theory, combinatorics, graph theory, and many other areas of mathematics. He also was a master collaborator: he would work with mathematicians at one university to discover theorems and write papers until he had exhausted his hosts, at which point he would fly to a new location and begin again. And while popular belief has it that a mathematicians’ ability to produce groundbreaking work slows or stops in middle age (the Fields Medal, known as the “Nobel Prize of Mathematics” is the most blatant manifestation of this belief: it is only awarded to mathematicians under the age of 40), Erdős was developing novel mathematics until his death in 1996, two months before I was born. In all, he published over 1,500 papers, a quantity which has never—and possibly will never—be surpassed.

In addition to his mathematical genius and unparalleled collaboration, Erdős was well known for his eccentricities. He rarely talked about anything besides math, had no interest in romance or a long-term partnership, worked fourteen-hour days with the help of incredible amounts of coffee and amphetamines, and could barely take care of himself, relying on his mathematical colleagues and their families for room and board wherever he went. All he owned—clothes, toiletries, passport, and papers—fit into one suitcase.

In addition to his mathematical genius and unparalleled collaboration, Erdős was well known for his eccentricities. He rarely talked about anything besides math, had no interest in romance or a long-term partnership, worked fourteen-hour days with the help of incredible amounts of coffee and amphetamines, and could barely take care of himself, relying on his mathematical colleagues and their families for room and board wherever he went. All he owned—clothes, toiletries, passport, and papers—fit into one suitcase.

This man is so fascinating, it’s too hard to resist elaboration. Here are a couple of illustrative stories from a book written by Paul Hoffman called The Man Who Loved Only Numbers.

Erdős was obsessive about his commitment to mathematical discovery. Once, a fellow mathematician confronted him about his frequent use of Benzedrine, an amphetamine, and told him that he should receive addiction treatment. Erdős disagreed, he was not addicted. The friend laughed and said he must be joking. So to prove his point, Erdős stopped taking any stimulants for a month. When he was done, he called up the mathematician friend, told him that he had completed the challenge, and asked if his friend felt guilty for setting mathematics back a month. Then, reportedly, Erdős took some Benzedrine and began cranking out mathematics like before.

Erdős was also notorious for his inability to do laundry, cook, or generally take care of himself. On one occasion, he was staying at a house of a mathematician colleague whose wife noticed something strange happening. One morning, his colleague’s wife came into the kitchen and saw the floor covered in cereal. It must’ve been difficult to make such a mess while fixing a bowl of cereal, she thought, but didn’t say anything because she expected this sort of thing with Erdős. So she cleaned it up and let the matter be. However, the next morning, she encountered the same scene in the kitchen. Cereal everywhere. She walked into the study where Erdős was working and asked him what had happened. He told her. Apparently he had wanted to help out, so he decided to feed the dogs. Not knowing what they ate, he took fistfuls of cereal and dropped them on the floor. His explanation complete, Erdős went back to work. Then he turned back. The dogs didn’t seem to want any, he added.

Perhaps my favorite characteristic of Erdős was that children loved him. When he visited colleagues, he often asked about and greeted their children first. He treated them as he did adults, and posed mathematical questions that challenged and excited them. Oftentimes, he said, they could come up with more creative approaches than their parents.

Erdős, lovably eccentric and incredibly intelligent, is one of the great heroes of Hungarians.

~ ~ ~

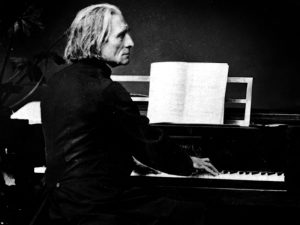

The Composer and Virtuoso

[Note on language: “s” in Hungarian sounds like “sh” in English, and “sz” sounds like “s”. Once you know this, you sound twice as Hungarian when you speak. This is why “Budapest” is “Buda-pesht” and “Liszt” is “List”. Look, you’ve got it—you sound Hungarian already!]

Ferenc (Franz) Liszt may be the greatest pianist who ever lived. Born in 1811 in Budapest, he began piano lessons in early childhood and was performing professionally by the age of seven. He was ambitious and talented, and attracted attention from several of the most famous composers of the era: Salieri was his piano instructor for a time and he met Beethoven and Schubert in 1822. At twenty-one, he found his professional calling when he went to a recital of Paganini, the great violin virtuoso. He decided on the spot that he would become as great a performer on the piano as Paganini was on the violin.

During the 1840s and 1850s, Liszt crisscrossed Europe giving performances. He also composed some of his most famous pieces during this time (see the three pieces selected below, you’ll probably recognize them). In recital, he was known as a showman, taking liberties with music that many musicians would consider sacrilegious. He was also such a frequent performer that he was often the only pianist available with new music during his tours. With no one to join him on the program, he became the first concert pianist to give solo recitals. My piano professor at Whitman, Dr. Wood, has also mentioned that we owe the tradition of memorizing music to Liszt. According to Wood, he would show up in a town and ask what piece they wanted to hear, and then play it from memory. Concert pianists across Europe followed his lead and the practice took hold. Thank you Liszt, but for my brain’s sake, I wish that you hadn’t.

After traveling Europe for years, Liszt settled down in Germany. The Austro-Hungarian government was disappointed, and decided to lure him back to his home country. In 1871, the idea for a Royal Academy—with Liszt as its president—was conceived. He would perform, direct the national orchestra, and teach classes at the Academy for most of the year. Liszt took the position, but didn’t complete many of his duties (he didn’t direct the orchestra, and he left Budapest before finals were completed every semester). The prospect of recitals was simply too enticing. However, he did inspire a generation of Hungarian composers and helped to solidify a tradition of piano mastery that continues in Hungary to this day. He continued to perform for most of the rest of his life.

The Liszt Playlist (or should I say, Playliszt?)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LdH1hSWGFGU Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 (around 6:06 is when I began to recognize the melody—look at those hands!)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KpOtuoHL45Y Liebestraum – Love Dream (possibly Liszt’s most famous piece)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0FbQZCsYXVg La Campenella (future hair goals)

If you want more, just visit Spotify’s Liszt page. https://open.spotify.com/artist/1385hLNbrnbCJGokfH2ac2

I’ve found that his music is excellent for studying—I listened to it while writing my blog posts.

~ ~ ~

Shout out to those of you who made it this far! Until later, loyal readers. Thank you so much for learning about Hungary with me! During these next couple weeks, feel free to email me (larsonnd@whitman.edu) with topics that you’d like to hear about.

Next week, a tour of my apartment and a Hungarian lesson!

Nathaniel