I returned from our program’s excursion in Bosnia-Herzegovina (BiH) 2 weeks ago, and I am still processing all that I experienced and learned. This program is incredibly intensive, and the content we discuss and learn about is not light. This trip to BiH was no exception – the war in Bosnia was the bloodiest of the Yugoslav conflicts.

As for the title of this post – BiH is an absolutely breathtaking country, especially at this time of year! Driving from Belgrade to Banja Luka and then to Sarajevo and Srebrenica, we passed through huge mountains, colorful trees, quaint farms and peaceful creeks (see the pictures below). This country is so beautiful, it is hard to imagine that such horrific things could occur on this same land.

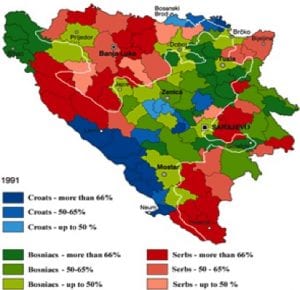

Before the conflicts, BiH was a multi-ethnic state – composed of Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), Serbs, and Croats, living all together in a single Yugoslav republic (see the map below). Thus, with the breakup of Yugoslavia pitting Croats against Serbs and Serbs against Bosniaks, etc, BiH suffered significantly. The war resulted in a divided state, with most territories ethnically cleansed (see second map).

Left: ethnic make-up of BiH before the war (1991); Right: ethnic make-up of BiH after the war (1998)

I was first introduced to the complexities of post-conflict, former-Yugoslav societies through a book titled The Politics of Exile. This book navigates academic theories of ethics in the context of real experiences in the Bosnian war, ultimately concluding “that we all laugh and mourn and love and hate with the same breath of air in our lungs. We are guilty and innocent.”

Dauphinee, the author, reveals the difficulty in applying these academic theories to real world experiences, especially in communities still drenched in the emotional and traumatic aftermath of conflict. This left me conflicted towards the prospect of studying on a “Peace and Conflict Studies” program in a place and culture which I’ve never experienced. What does the field of peace and conflict studies entail and can it even capture the realities of life in these post-conflict societies?

At first I thought that reading more about the historical and political specifics of the conflict in the Balkans would illuminate my understanding of how peace is fostered, however, I’ve begun to realize that perhaps no one has the answer at all. More than two decades after the war, these communities I’m learning about are still deeply divided and entrenched in corruption and seemingly endless social complexities.

BiH seems to be the most severe example of this. The country’s constitution today is still merely the peace agreement which ended the war – and was written by international communities (*cough cough* the USA) and written in Dayton, Ohio! This was meant to be temporary, yet 22 years later, it remains the constitution. This “peace agreement” divides BiH into 2 rather ethnically homogenous entities – Republika Srpska (majority Serbs) and the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina (majority Bosniaks and Croats). The presidency of BiH rotates between 3 presidents – a Serb (elected by the people of Republika Srpska), a Bosniak, and a Croat (the last two elected by the people of the Federation). If you’re confused already, which I’m sure you are – remember this is just touching the surface of the political complexity of BiH.

In BiH before the war, different ethnicities lived next to each other, there were many mixed marriages, and relative peace. Yet today, the separate entities have maintained the distance between different entities, and mixed marriages are rare. I spoke with some Bosniak students at a university in Sarajevo, and asked them if they are friends with Serbs or Croats. They told me that they are not opposed to being friends with them, but it is difficult to avoid the stereotypes or judgements from other groups. They said from the moment you introduce yourself, your name tells the other person what ethnicity you are, and this immediately can trigger specific perceptions related to that identity.

To be honest, my visit to BiH left me feeling hopeless about the possibility of peace-building, especially after visiting the memorial of the victims of the Srebrenica genocide. After watching a documentary on the genocide, we discussed the conflicting narratives surrounding this defining event of the breakup of Yugoslavia with a researcher in BiH. She explained her research interviewing Bosnian Serb women about their experiences during the war and the Srebrenica genocide. This perspective is often left outside of the portrayal of these events, yet holds valid arguments against the common placing of blame on the Serbs, and the Serbs only. The fragility of defining a clear perpetrator and victim in these events represents much of the society today – responsibility is rarely accepted and memories are manipulated to reinforce nationalist agendas, which still dominate politics.

Above: the memorial for the genocide at Srebrenica, where over 8,000 Bosniaks were murdered by the Serb army. Srebrenica was a UN designated “safe area”, yet was not protected by UN peacekeeping soldiers when the Serb army invaded. *the situation is a bit more complicated than that, I encourage you to do some more research…

These attempts to foster peace through memorials and commemorations seem to lead to fiercer tensions, rather than constructive conversation. As I learn about the past conflict and its continual detrimental effect on this region, it’s hard to see how “peace and conflict studies” can be put to real work on the ground.

But while I’ve given a very pessimistic outlook on the issues I’ve been learning about here in the Balkans, this does not give the full picture. In the face of these hardships and cruelties, I have discovered the incredible resilience of people. At the Historical Museum of BiH and the War Childhood Museum in Sarajevo, I learned of the persistence and strength of the victims of war – both during the conflict and in sharing their stories after. It has been inspiring to visit NGOs and meet people who are working tirelessly to build peace in these communities, and I hope their work will continue to progress. Despite being uncertain and critical of the nature of peace and conflict studies, I have faith that people genuinely desire peace and will eventually find an answer – however idealistic that may be.

Bella,

Once again, great post! I really got a sense not only of the complexity of the conflict and it’s aftermath but also I’ve you’re exeperience. Could you elaborate more on what you were saying about the Bosnian Serb women?