Coming back for spring semester at Whitman is, well, strange to say the least. For starters, I only got three weeks to re-acclimate to America over Christmas break. Since I stayed in China to travel with my mother after my semester abroad was finished, I actually had less time than other fall study abroad students to get back in the swing of things. Trust me, those extra few weeks make all the difference.

I didn’t experience much culture shock when I arrived in China and so I had no idea what to expect when I returned to the US. As it turned out, reverse culture shock hit me like an unexpected hammer. I would find myself falling into China habits without thinking. I would unconsciously turn on my VPN every time I turned on my laptop. I did laundry five days in advance because I was still on my no dryer schedule. I used chopsticks to cook, craved bubble tea (I miss my Coco!) like crazy, and spoken in Chinese to people on the Whitman campus without thinking.

Not only did I have to break my China habits (and cravings), but I had to play catch up at Whitman. My semester abroad was the first semester that I had not taken a science class. I am currently taking three of them (biochemistry, genomics, and evolutionary biology), so I definitely feel like I lost a step (or two). I see a lot of people around campus that I don’t recognize, especially in orchestra, and it periodically hits me that I missed quite a lot while I was gone. We all joke about the Whitman bubble but I feel like study abroad is a bubble as well. You are so removed from America, some more than others, and your home college that it’s easy to forget that life moved on without you. New freshmen are already settled, I missed the orchestra playing with Dr. Dodds, and all of a sudden you can rent textbooks at the bookstore. There is so much that changed here at Whitman that I missed that it sometimes feels like I am a freshman all over again. Not that I didn’t miss Whitman while I was away (I did, I promise), but it’s only now that I am back on campus that I see how different things are.

However, it took me a while to see the changes in myself. Oh sure, I knew that my Chinese had really improved and that I had learned a lot about Chinese culture and history, but the internal changes were the ones I was blind to. I’ve often thought that it’s easy to see change in others, but it’s hard to see them in yourself. I found that to be true for me upon my return to Whitman. My new view and understanding of China carried over into my everyday life. It wasn’t just that I now know about Xi Jinping’s policies or that I have first hand knowledge Chinese calligraphy; it’s that I think more critically about certain things. Race and ethnicity takes on new meaning for me. I’d never really thought about what being Asian-American meant to me on such a deep level until I was knee deep in a country where hyphenated identity doesn’t exist. Suddenly I was having to explain, and even defend, my identity to everyone I met. As I justified my own identity to almost every Chinese person I met and talked with, I grew into a habit of thoughtfulness. I started thinking about how much of who I am was truly rooted in my view of myself, and how much was simply a reflection of how other people saw me.

Although when I really think about it, I suppose I shouldn’t really be surprised. Studying abroad isn’t just about taking classes in a new place or learning about a new culture. It is more than learning another language, making new friends, or even traveling. The truth of study abroad is that it is a test of your personality. You get to see if you can be an adult in a whole new place where everything you know is out of reach. You are on your own and it is scary, crazy, and wonderful all at the same time. You learn things about yourself that you would have never considered while in your comfortable little bubble. I still have no idea what my future holds, and you know what? That’s alright. Having all the answers all the time would make life boring. Life is a series of questions; studying abroad was stepping stone towards finding the next one.

Bonus: pictures from my after semester trip with my mother!

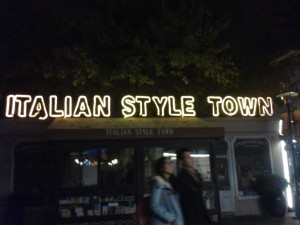

Top left: Drum tower, Xian, China Top right: Muslim street, Xian, China

Bottom left: Potala palace, Lhasa, Tibet Bottom right: Ice and snow world, Harbin, China